LEARNING to KANTEI

The most memorable phrases often repeated to me by my nihonto sensei's are "Just keep looking at the swords"

and "Only look at good swords". This age-old advice, given by the

godfather of sword study Dr. Kanzan Sato, is still as

true today as it ever has been. The only problem is that in

I have always known that "The Connoisseur's Book of Japanese Swords' was

an invaluable aid to my sword studies. An excellent translation by Kenji Mishina sensei, of the notes made and published by his own teacher, Kokan Nagayama sensei. It was originally meant as a guide to kantei (appraisal) for the students of the Honami school of polishing.

The notes at the back and the explanations for kantei

scoring are a great help to collectors. There are pages of notes of which

characteristics are used by which smiths. This immediately narrows the field of

search for a novice collector. Another popular kantei book is called 'Shin Nihonto Kantei Nyumon - The New Introduction to Kantei'.

It is co-written by the editor of the Shunju press (a

Japanese sword newspaper) and Head of the Tokyo Chapter† of the NBTHK, Mr. Kazou

Iida along with Mr. Yuichi Hiroi formerly of the

Agency for Cultural Affairs. One of the strong points of this book is

that it has some practice test cases for kantei from oshigata. Another web-book which is often used alongside

either of these books is the Koto presentation by Robert Cole, Sho-Shin web site.

Oshigata are also a very valuable learning tool when

it comes to Appraisal. There is no substitute for the real thing, but if you

live in the

The 'Connoisseur's Book' explains the scoring system used for 'Kantei'. 'Iya' means that you have something important right: The

period. It also means you have the wrong part of the country. If you

should make a successful proposal, you will receive 'Atarai

- correct'. If your proposal identifies the teacher or student of the smith in

question, you will receive the score 'Dozen'. If you receive 'Douzen' do not make another

attempt, as you may go the wrong direction. If you receive the score 'Kuni iri yoku'

this means that you have the period and the province correct. This allows you

to consult your kantei book to see which other schools were operating in that

period. Then you can adjust your proposal. There are several

combinations of all these marks, all of which can be found in the Nagayama book.

Giving appraisals on blades can be a serious business. However, learning to kantei can be fun and not the confidence-damaging skill it

can sometimes appear to be. If something is more enjoyable, we often speed up

our learning curve. I have come to realise that

this 'kantei-game' is actually a valuable tool for sword study - as long as you know

what you want from it at the end of the day and you do

not lose sight of what is a good sword. I have heard that there are people who

are fantastic at separating and diagnosing the characteristics of a blade in

order to give the perfect appraisal, but cannot determine a fine sword, which

goes to show the need for balance.

Kantei is important to sword study and can be good

fun, but it is only one aspect. The study of

Japanese swords is ultimately a personal journey, one of which can be a spiritual one. Swords are sacred in

Basic Characteristics of HADA

Konuka-hada from a mainline Hizen-to |

Masame-hada from a blade papered to Hosho |

Ko-Itame hada with brilliant ji-nie |

Itame-hada |

Itame-hada with Chikei | |

Basic Characteristics of HAMON

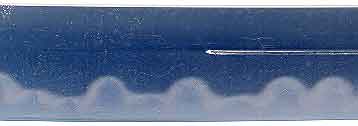

A Choji hamon in nioi with extensive sunagashi |

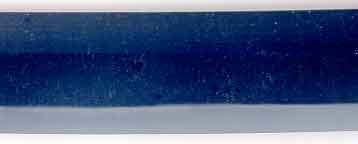

A Choji-midare hamon on a Bizen-to with strongly stated kinsuji |

A Hoso-Suguha hamon |

A Chu-Suguha hamon on a Hizen-to |

A Midare (irregular) hamon | |

| Below are some variations of the most commonly seen hamons. There are many different types when one studies the entire history of sword making. However, most swords will have at least part of one of the examples shown below within the main portion of the temperline. |

|

Mino Style gunome midare. Blade is from the late 1500ís, and is made by the famous Seki smith Kanesada. Well shaped and very bright hamon shows the quality of this sword easily. |

|

Soshu styled notare midare. Blade is from the 1700ís, made by a smith that worked in the Soshu tradition. Famous Koto Soshu smiths worked in a similar hamon, but with more, higher quality nie. |

|

Yamato/Yamashiro styled straight (suguha) hamon, many smiths worked in this tradition. |

|

Bizen styled choji midare. This type of hamon is very popular among sword enthusiast. |

| Suguha

(straight ) - Used from the beginning of Japanese sword manufacture to

present day. Used by all five main schools (Gokaden) with different

variations.

Midare - Heian period to present day. Ko-midare, choji midare, notare midare, gunome midare, O midare, hako midare, sudare midare, doran gunome midare, yahazu midare, mimigata midare amd hitatsura midare. Choji (Clove Pattern) - Used from the late Heian period to present day. Many types were used and developed. Juka choji, kawazuku choji, saka choji are just some of the variations that were developed. Gunome - Used from the Kamakura period, but different variations were developed from the original design during the Shinto period, especially the hamon known as gunome doran used by the Sukehiro School. Kanemoto made the sanbon sugi (3 cedar zig-zag) gunome hamon famous for its cutting ability during the Muromachi period. Notare (Billowing wave) - Used from the late Kamakura period to present day, but ko-notare was seen in earlier periods as part of some hamons. The Soshu School was well known for using this within their hamons. Hitatsura (Full) - Used from the late Kamakura period by the Soshu School, but became popular during the Muromachi period by most of the other main schools. Rarely seen in the late Shinto and Shinshinto period, even fewer during the gendaito periods. |

References:

Richard Stein, Nihon-to Art, Ricecracker, and Sho-Shin.com

Return to GALLERY or STUDY GUIDE